There is something almost religious about it, and Chuck Berry knows it. “I’m not an oldies act,” he said when he turned 75. “The music I play, it is a ritual, something that matters to people in a special way. I wouldn’t want to interfere with that.”

So in October 2010, I go to St. Louis again. There will be two shows, one at The Pageant, and one at Blueberry Hill. Rebecca, an actor, is in rehearsals and can’t join me. My two younger kids wouldn’t be allowed into Blueberry Hill. My elder daughter, Jade, is about to become a mom, so she’s not going anywhere for a while. But my brother Paul and his wife Liz agree to meet me in St. Louis. Paul spent time in Missouri as a kid. Liz grew up bopping to Jimmy Reed. I find it odd but wonderful that they are willing to join me on my eccentric pilgrimage. I have plans to tour St. Louis looking for the landmarks of my hero’s past. I want to see the houses and neighborhoods where he grew up, and the clubs where he played. Paul and Liz are game, as long as they can get in a few games of golf between times.

We arrive on separate flights. I text Bob Lohr that we are in town and he invites us to a 3:00 pm sound check. It’s already 2:00 when we speed off towards The Pageant in the rental car.

We’re staying at the Moonrise Hotel, next door to The Pageant, and a few blocks east of Blueberry Hill. All three establishments are owned by Chuck Berry’s friend Joe Edwards. We check in and head quickly to The Pageant, but it’s locked up tight, so we stroll up Delmar towards Blueberry Hill, thinking the sound check is not in the cards. Then I check my phone and find four or five voice mails from Lohr beginning with a polite tone, then increasingly emphatic. (The last is something like “get your asses down here, we need to start!”) We hurry back and find Bob waiting on the east side of the building. He hands us passes and we follow him through a side door and onto the stage.

The interior of The Pageant is stunning— a simple but beautiful space with a dance floor in front of the stage, raised seating at tables all around that, and a U shaped balcony. Every seat appears to be a good one, and there’s a dance floor in the front. That’s where I intend to be.

As we stand there, I begin to realize that my blog, which at times I feel silly about, is bringing me closer and closer to where I wanted to be as a child. A few months before Lohr was in my living room. Now I’ve got a backstage pass. It’s possible that later in the evening I’ll be able to meet Chuck Berry again. This time I’ve learned from Rafferty. I’ve got a gift for him, a copy of the drawing I made when I was 17, the one of him as a child from the cover of “Bio.” It’s framed. I don’t want an autograph—I want to give something back.

I feel pretty lucky.

I wave at CBII. I’ve never met him in person, but we’ve communicated a bit. He’s busy but waves back. Chuck’s long time bass player and de facto musical director, Jim Marsala, comes and welcomes us. I’m surprised to learn that he remembers an e-mail I sent him. I introduce myself to Keith Robinson, telling him that he’s the best drummer I’ve seen play with Chuck Berry.

Most of the sound check is done individually, but before they finish they invite Thomas Einarson, a musician visiting from Sweden, to fill the spot Chuck Berry's guitar will take later in the show. Eainarson is a commited Chuck Berry fan. His band, "Bad Sign," has opened for Chuck Berry at Blueberry Hill. He is also one of the rare individuals to be trusted with Chuck Berry's guitar. I'm hoping he'll pull it out, but instead he uses a Fender to play some very authentic licks. It's a nice moment.

Most of the sound check is done individually, but before they finish they invite Thomas Einarson, a musician visiting from Sweden, to fill the spot Chuck Berry's guitar will take later in the show. Eainarson is a commited Chuck Berry fan. His band, "Bad Sign," has opened for Chuck Berry at Blueberry Hill. He is also one of the rare individuals to be trusted with Chuck Berry's guitar. I'm hoping he'll pull it out, but instead he uses a Fender to play some very authentic licks. It's a nice moment.Lohr tells us that the “all access” passes will get us into the hall as soon as the bar opens at 5. We get back early and enter through the stage door. It’s a curious feeling when the guards wave us through.

The Pageant is empty. We find places at a bar about 30 feet from center stage with a direct sight line over the dance floor. A waiter or bouncer approaches. He seems annoyed.

“I don’t know how you got in, but we’re not open,” he says, with authority.

We flash our “all access” badges. “I’m sorry,” he says, and leaves us in our majesty.

And then, finally, it starts. I’m not at the bar anymore—I’m up front, as close as I can manage to get to the center microphone. The man next to me has brought his son from Georgia for the show. To my left, at a table near the dance floor, is a large contingent of Berrys. (I see Chuck Berry’s wife, whom I recognize from her brief, stunned appearance in the film “Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll.”) I like that the hometown audience is more racially mixed than the other Chuck Berry shows I’ve seen over the last 40 years.

Two girls too cute to be a minute over 17 are craning their necks, searching the wings for Chuck’s grandson. I suspect they are cousins or school chums. A lot of young hipsters are there, and a lot of old folk. A mother pushes two other high school girls—sweet little sixteens— into a position next to me.

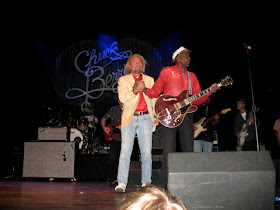

Joe Edwards and a co-owner of The Pageant come out to make the introduction. There’s a giant birthday cake, but it’s for the theater, not Chuck. (The Pageant is ten years old this evening; Chuck will be 84 the next day.) The band stands ready. And then here comes Chuck Berry, black slacks, a glittering red shirt, an admiral’s cap and that scratched up, taped up old guitar. He grabs Edward’s hand and pulls him close. Edwards walks off, grinning, and a Chuck Berry show begins.

How often has this happened? There’s no authoritative or complete listing of the shows he has performed in his 60 years as a professional. Author Morten Reff lists as many of the international shows as he could find and it is a bigger number than I care to count—well over 500. But I can make some reasonable (and I think reasonably conservative) estimates. Let’s assume that from 1955 until 1961 he did an average of 200 shows a year. That makes 1200. Let’s say that from 1963 until 1971 he worked a little harder—say 225 a year. That’s another 1800. Then comes his “Ding a Ling” and even more work—let’s say 750 shows over three years. We’re up to 3750. Then let it cruise at 125 shows a year for the next 10 years. That’s probably conservative, but it’s now 1986, and we’re at 5250 shows. But he’s only 60 and still going strong. Let’s assume 100 shows a year until he turns 70, 75 a year until 75, 50 a year till he turns 80, and then slow him down to something like 25 shows a year when he enters his 80s. By my reasonably well educated (and carefully manipulated) fantasy count we’re at 7000 shows and counting.

It’s guesswork on my part, but you get the idea. The man worked. This isn’t someone who plays golf 300 days a year and then regroups for a tour every ten years to refill the coffers. If there’s nothing else you take from this reading, take this: the man worked, and still does.

So here I am, at show 7001, and I know, from the first notes, that it will be special. Tonight, on the eve of his 84th birthday, Chuck Berry is young again. His eyes shine. His look is devilish. His guitar intros are perfect. He is hitting all the riffs, hitting them on all cylinders, and he knows it. He looks almost surprised, and absolutely delighted.

The view from stage must be fine. The Pageant is full. The people are happy. He starts with "Roll Over Beethoven," hitting every note of the introduction, showing us his “blue suede shoes” twice, moving back and forth across the stage and nailing every guitar part. He chugs straight into the chords of "School Day" and we all “hail! hail!” the music he invented. He plays "Memphis," singing about a lost daughter, with Ingrid on stage to back him. When he starts "Carol" he must not like the first few notes, so he stops and starts again and gets it right— and then starts doing what Mr. Richards thought impossible exactly 24 birthdays earlier, playing both lead and rhythm. For a time “Carol” becomes “Queenie," and he’s “still thinking” (“I do that sometimes!”) but then Carol’s back, and he’s frantic, thumping on the strings of his guitar like the head of a drum. The night’s emotion works on him. There’s a moment he sings "oh" to Carol so long and plaintively you think he might cry remembering when that girl was hard to get even for him! Then he gives his 84 year old body a break and gives us all an education in the blues with “Wee Wee Hours.” Ingrid bends at the waist and blows her harmonica. Bob Lohr does the riff that Chuck tried and failed to teach a piano player in Seattle and trills and flourishes that hearken directly back to Johnnie Johnson. If Chuck Berry had written and recorded just this one song he would have a place the blues encyclopedia. But he wrote dozens, and after opening the floor for requests he responds with "Nadine," chugging away at its familiar bass riff as the girl slips into her macchiato Cadillac. During "Rock and Roll Music," he gives a lyrical twist to the lines about modern jazz. His singing is youthful tonight. He’s not just shouting the lyrics rhythmically, an interesting style he’s adopted in recent years. He’s singing, bending notes the way he bends the notes on his guitar, savoring rhymes he invented so many years ago he sometimes forgets them, grinning devilishly at the double entendres. He ends “Rock and Roll Music” with a powerful cha cha cha of strummed chords, then starts a blistering rendition of "Let it Rock." He takes another breather by trying a verse of a stage rarity, “La Juanda,” but lets go of it quickly to finish with "Reelin' and Rockin'," which doesn’t last till the break of dawn, but goes on a long, long time and includes the closest thing to an encore that I've seen Chuck Berry do. He gets most of the way off stage, then returns to sit on the drum riser and play a while longer. Then a bit of "House Lights," and he’s done.

I don’t take notes but there are moments I can remember without them. He does his famous scoot twice, then starts a third time to coax his grandson into trying it. Charles III, is playing the third guitar. Daughter Ingrid, in tight, black leather, is singing harmonies and wailing on harmonica. Adopted “son” Marsala seems pleased, grinning cheerfully throughout the night. Chuck’s extended family is hooting and hollering from the dance floor. It’s an all ages show, and the Berry family contingent includes little kids. His “rock and roll children” are there, too, some nearly 70, some still sweet, little and sixteen. The night belongs, in many ways, to Lohr, who plays at least a half dozen extended solos on his digital keyboard. There’s a special moment at the end when CBII and CBIII move to the front of the stage and play together, heads bent in concentration. There’s another special moment when Ingrid finishes a solo then walks towards her dad on stage. I see him lock eyes with her and mouth the words “I love you.”

And that’s how I feel, too, not just about Ingrid, but about her dad, about his music, about his band, about the night we’ve just experienced, the whole spectacle and ritual and this amazing rebirth and rejuvenation of my old hero. I’ve experienced it again— an apparition, like the Virgin of Guadalupe or the Lady of Lourdes—our Father of Rock and Roll, young again, at age 84.

(This is Chapter 30 of a book length publication about how Chuck Berry turned my life upside down. The next chapter is HERE. To start reading from the beginning, look for the Prologue and Chapter One HERE.)

33/43 5/13/13/8/08/a

I hope I can see him before he dies.

ReplyDeleteI was so close this year but at the last minute he was replaced by Pat Boone. Yes I said Pat Boone.

Long Live R&R-- Get down to Blueberry Hill at least once! It happens every month.

ReplyDeletePat Boone!

Ah well....

I want to buy your book! Great piece Peter and, for me, the "macchiato Cadillac" was the cherry on top!

ReplyDeleteCarmelo

Carmelo-

ReplyDeleteGrazie! And the whole "book" is right there! Free! A lifetime of Chuck Berry worship in 34 easy chapters!